“Lady” Journalists

“Boys don’t like girls who are too smart.”

“What the hell would I want a girl for?”

“We agreed that women were a nuisance in the office, anyway.”

Consider the Source: “Lady” Journalists and War Correspondents of the 20th Century

Just as Rosie the Riveter found work in the factories during World War II, Rosie the Reporter started reporting and writing. Many of the gains made by women journalists though were reversed during after the war.

By the 1960s, women could be hired at major newspapers, but they had little room for growth. These women typically were restricted to the women’s pages, typically a low-status department.

“It came down to her gender: she didn’t belong because she wasn’t a guy.”

-Elizabeth Becker, Journalist, Author and War correspondent

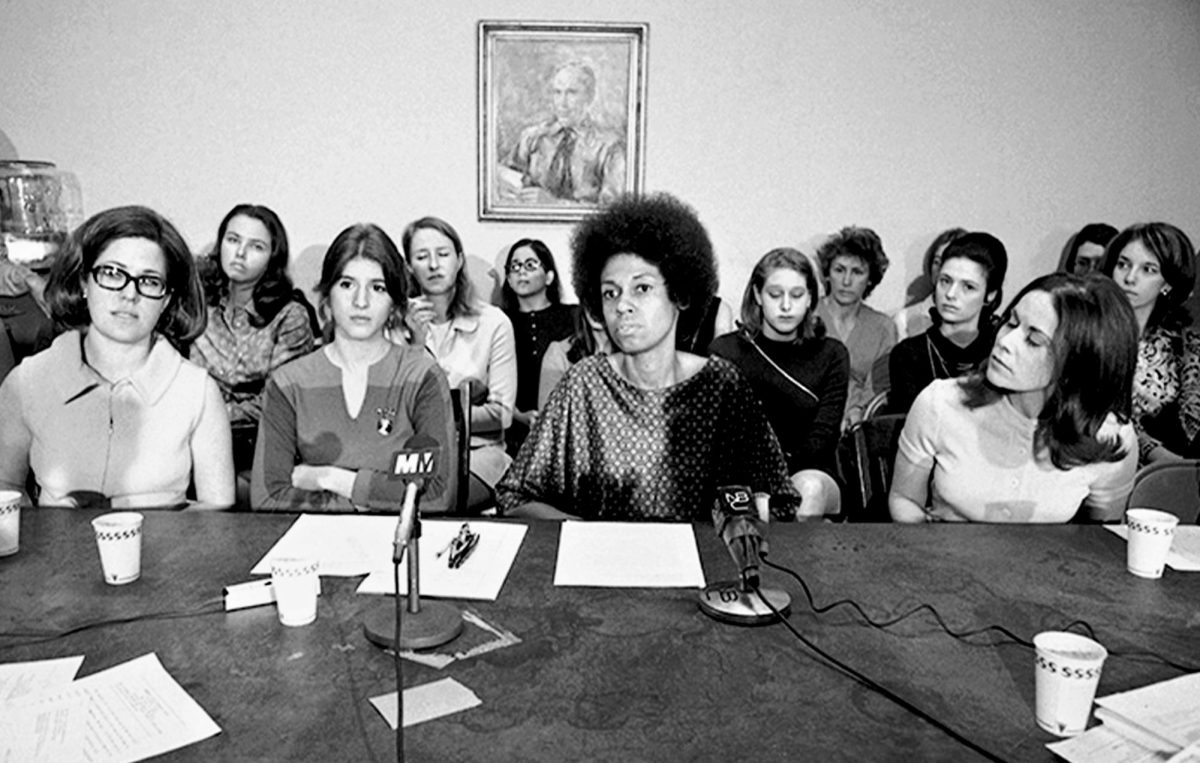

Journalism in the 1970s changed because of social, political and technological shifts, along with the increasing influence of women and marginalized groups in the industry.

The rise of the feminist movement and civil rights activism sparked a push for more inclusive and diverse representation in the media. Women journalists began to challenge traditional roles and fought for equal opportunities, eventually breaking into high-profile positions.

The sex provision of Title VII was not the only one to get a workout in the 1970s. Race discrimination cases were filed at “The Washington Post” and

“The New York Times,” citing complaints like those of the women, but this time on behalf of minority employees.

The Reader’s Digest, Associated Press and The New York Times companies’ agreements all made headlines because of the large cash settlements won by female employees.

Despite these concessions, once the settlements were signed, the newspaper management maintained they were not guilty.

Regardless of their insistence, the programs did increase the diversity of newsrooms in the late 1970s and into the 1980s.

As for the “Newsweek” women, they settled in 1973. Plaintiffs who participated in these lawsuits experienced negative outcomes. They were professionally sidelined by their employers, while others reported missing out on future jobs. Many agreed to sign a lawsuit only after they had left an outlet and were safely employed elsewhere. Some left the industry entirely.

“Women in the media don’t just report the truth; they must create it. The role of women in the press is as vital as the stories themselves.” -Betty Friedan, Journalist

The “Girls” at the Desk

Alice Dunnigan became the first Black woman to receive press credentials at the White House. Dunnigan started her journalism career by writing one-sentence news items for the local Owensboro Enterprise newspaper at 13 and completed the 10 years of education available to Black Americans in the segregated Russellville School System. She juggled a freelance writer position for the American Negro Press while attending Howard University. She broke barriers but faced challenges throughout the 1970s while working tirelessly to give voice to Black Americans in journalism. Dunnigan’ paved the way for more inclusive reporting.

“While the role of the Black press, like other newspapers, is that of objectively reporting the news, it has had another function equally important, that of fighting oppression. Without Black reporters on the national scene to report the fight for civil rights, equality and justice, the deeds, efforts and struggles would forever be lost to history.” -Alice Dunnigan, Journalist

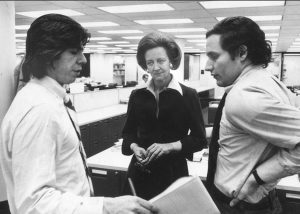

Katharine Graham Despite her eventual leadership at “The Washington Post,” Katharine Graham battled pervasive sexism that limited women’s access to key editorial roles. Famously among the first female publishers of a major American newspaper, Graham led “The Washington Post” into the era of television reporting and investigative journalism, elevating it among the nation’s foremost news outlets. She survived an abusive marriage and her husband’s suicide before gaining control of the newspaper while raising four children. Her publishing decisions put her reputation and business at risk. Aware of the stakes, she fought to uphold the First Amendment. She would take the fight as far as the Supreme Court to preserve the integrity of journalism. Before printing another devastating article uncovering the extent of the Watergate scandal, Nixon’s Attorney General John Mitchell said, “Katie’s gonna get caught in a big fat wringer if that’s published.” Graham replied, “No one calls me Katie. Run it.” “The Washington Post” is still counted among the most influential newspapers in the United States.

Marlene Sanders worked for ABC in the ‘60s and ‘70s and moved to CBS in 1978. Sanders was the first woman to achieve several milestones in the then male-dominated field of television news. At a time when opportunities were scarce for women in network news, Sanders got the chance to anchor when the regular got sick.

“She had to fight a lot of stereotypes and a lot of ridicule,” said Bill Moyers, who worked with Sanders. At the time, she had an afternoon show called ‘News with the Woman’s Touch.’ Food, fashion, child-rearing, decorating, social events and the entertainment scene were all you could expect.” Gradually, Sanders was awarded more hard-news assignments.

As the women’s movement grew, Sanders saw her chance to make a difference. “In the initial phase of the women’s movement, reporting on it was done mainly by men, and it was snide, hostile. Women’s lib was treated with humor at best and contempt at worst.”

“I felt like I was jumping into a rapidly moving ocean, and I had to jump in with a lot of white men who were seriously anxious to hold on to their power.” -Dorothy Gillman, Journalist

Dorothy Gillman In 1957, Dorothy Gillman became a reporter for the “Memphis Defender.” She was hired by editor Alex Wilson. During the 1957 Little Rock Nine school desegregation crises, Wilson, who had gone to report the story, was beaten by a white mob, she witnessed the beating on TV back at the Defender’s office. She was shaken into action. Despite Wilson’s warning that Little Rock was no place for “a girl” reporter, she insisted on going to cover the story.

“I decided to train to be a journalist, and I was able to go to Lincoln University, Missouri, but at each step, white supremacy was just always pushing hard against us.” Later, Gillman earned her master’s degree at the Columbia School of Journalism and was hired by “The Washington Post.” She was only 24 and the first African American woman to be hired as a reporter by the paper. “When I first arrived at ‘The Washington Post,’ I overheard one of the old-time editors say, “We don’t even cover Black deaths because they’re just cheap deaths.” To hear that kind of horrible statement coming from a newspaper editor is a good example of how deep this whole system was in American society.”

In addition to her career at “The Washington Post,” she has been an activist helping to organize protests against the “New York Daily” after it fired two-thirds of its African-American staff. She also was the president of the National Association of Black Journalists. “I remember when I was writing columns, it got very uncomfortable because I was saying things they didn’t want to hear, or they didn’t want to print,” Gilliam said. She created the Young Journalists Development Program, which was designed to bring more young people into journalism. Post journalists worked with students at local high schools, and in some cases, the Post printed the high school newspapers for the schools. Always an advocate for newsroom diversity, Gilliam continues to be vocal on the need for media to dismantle systemic racism.

“The critical role of the Black press in the Civil Rights Movement has not received the attention it deserves. Black journalists put themselves on the front lines before and during the Civil Rights Movement, doing the work and putting their bodies in danger so the sacrifices of activists would not go unnoticed. The nation needs to acknowledge and learn from the experiences of those who witnessed those early protests if we are to actualize Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream.” -Dorothy Gillman, Journalist

Ethel Payne First Lady of the Black Press, Payne was a fearless journalist and Civil Rights activist. She was the first Black woman to be included in the White House Press Corps. Payne was known for asking questions that other journalists did not want to approach. When the Korean War began, she wrote in her journal about the treatment of Black troops; the segregation, the slurs, the babies abandoned because they were born to Japanese mothers and Black fathers. Payne’s articles were met with criticism, and she was accused of upsetting the morale of the troops. When CBS hired her in 1972, she became the first Black woman commentator on a national network. She was known for asking tough questions that others didn’t dare ask, often breaking barriers in the field with her impactful reporting. She covered significant events, providing perspectives from a Black woman’s viewpoint.

“Had Ethel Payne not been a black woman, she certainly would have been one of the most recognized journalists in American society.” -The Washington Post

“The men always asked me, ‘Why do you want to be a journalist?’ As if a woman couldn’t possibly want to do something that had traditionally been a male-dominated profession,” -Helen Thomas, Journalist

Helen Thomas Reporter and author, Thomas was a long-serving member of the White House press corps. She covered the White House during the administrations of ten U.S. presidents; from the beginning of the Kennedy administration to the second year of the Obama administration. Thomas was the only female print journalist to accompany President Richard Nixon during his 1972 visit to China. One of the most respected female journalists of the era with experiences breaking into a male-dominated field. Despite access to the White House, she still faced relentless gender-based challenges. “There were plenty of men who would try to undermine my work.”

“You Don’t Belong Here”

Female War Correspondents

Catherine Leroy At 21 Leroy flew to Laos with her Leica M2 and $100. In a male-dominated field, Leroy defied societal expectations and embedded herself with military units, navigating dense jungles, wading through rice paddies, and parachuting into combat zones. Despite facing skepticism and being told that she didn’t belong, Leroy persisted, earning the respect of the soldiers. She was cool under fire, gravitated toward the thickest battles, went along on the soldiers’ slogs through the heat and mud. Leroy was the only non-military photographer and only woman to parachute into combat with U.S. forces in Vietnam. Afterwards, rumors circulated that she had slept with a colonel in exchange for permission. In fact, she had earned her parachutist license as a teenager and had already jumped 84 times. At a time when women’s liberation movements were still emerging, 4’10” and 85 pounds Leroy dodged bullets, bombs and abject sexism. Leroy took striking photos that gave America no choice but to look at the realities of war—showing what it did to people on both sides.

“Leroy was pushy, ambitious and shoving to get on a helicopter. She had no manners. She could be a hothead. When she didn’t get her way, she would flare up. She swore.” -Elizabeth Becker, War Correspondent, Journalist and Author

Frances FitzGerald paid her own way into Vietnam. She was an “on spec” reporter with no editor to guide her, no office to support her, and no promise that anyone would publish what she wrote about the war. She knocked out her first article on a blue Olivetti portable typewriter she had carried from New York and mailed it the cheap and slow way from a post office in the heart of Saigon’s French quarter to the Village Voice, nearly 9,000 miles away. It arrived, and on April 21, 1966, the Voice published FitzGerald’s indictment of the chaotic U.S. war policy.

“The result was a highly original piece written in the style of an outsider, someone who asked different questions and admitted when she didn’t have answers,” -Elizabeth Becker, War Correspondent, Journalist and Author

Photojournalist Dickie Chapelle was known for her work from WWII to the Vietnam War. She was a writer for the “National Observer” and spent much of her time on patrols with the Marines. Chapelle was killed on Nov. 4, 1965, while on patrol with a Marine platoon during Operation Black Ferret, a search and destroy operation The lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire boobytrap consisting of a mortar shell with a hand grenade attached to the top of it. Chapelle was hit in the neck by a piece of shrapnel which severed her carotid artery; she died soon after. Chapelle was one of history’s most fearless conflict journalists – and the first American woman to die on the job.

Photojournalist Dickie Chapelle was known for her work from WWII to the Vietnam War. She was a writer for the “National Observer” and spent much of her time on patrols with the Marines. Chapelle was killed on Nov. 4, 1965, while on patrol with a Marine platoon during Operation Black Ferret, a search and destroy operation The lieutenant in front of her kicked a tripwire boobytrap consisting of a mortar shell with a hand grenade attached to the top of it. Chapelle was hit in the neck by a piece of shrapnel which severed her carotid artery; she died soon after. Chapelle was one of history’s most fearless conflict journalists – and the first American woman to die on the job.

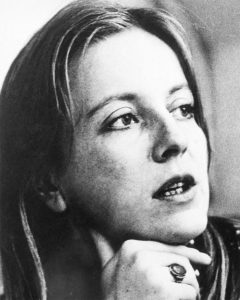

“We are all victims of this patriarchal system, and journalism is no exception.” -Gloria Steinem